Interview with Jane Kamensky, 2016 SHEAR James Bradford Biography Prize

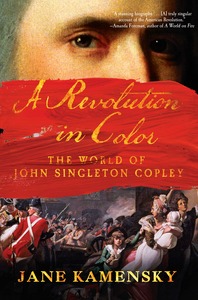

Jane Kamensky is Professor of History at Harvard University and Pforzheimer Foundation Director of the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. In addition to winning the 2016 James Bradford Biography Prize from SHEAR, A Revolution in Color: The World of John Singleton Copley (2016) was awarded the New-York Historical Society’s Barbara and David Zalaznick Book Prize in American History and the Annibel Jenkins Biography Prize of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies. It was also a finalist for PEN’s Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography, the Marfield Prize for Arts Writing, and the George Washington Book Prize.

Jane Kamensky is Professor of History at Harvard University and Pforzheimer Foundation Director of the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. In addition to winning the 2016 James Bradford Biography Prize from SHEAR, A Revolution in Color: The World of John Singleton Copley (2016) was awarded the New-York Historical Society’s Barbara and David Zalaznick Book Prize in American History and the Annibel Jenkins Biography Prize of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies. It was also a finalist for PEN’s Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography, the Marfield Prize for Arts Writing, and the George Washington Book Prize.

The Republic (TR): For those who haven’t read your book, would you please provide a synopsis?

Jane Kamensky (JK): A Revolution in Color tells an off-kilter story of British America in the age of the American Revolution through the biography of the New England-born painter John Singleton Copley. Born on the eve of King George’s War, Copley came of age in a thoroughly British Boston, with streets named Queen and King, and book stores and coffee houses touting the latest news from London. He identified thoroughly with an imperial imaginary, dreaming of a world in color an ocean away. When Boston grew heated over taxes in the 1760s, he identified as a Son of British Liberty, and hoped for a return of the status quo ante. He painted men and women on all sides of the conflict–Paul Revere and Thomas Gage, Samuel Adams and Francis Bernard–who doubtless gave him an earful while they sat for their portraits. But when shouting turned to shooting, he, like Melville’s Bartleby, simply preferred not to. Copley’s life and work make visible, literally visible, the viewpoints of that large group of early Americans whose preferred side in Britain’s American War was neither. As Yeats would say of another revolutionary conflict more than a century later, he thought “the worst [were] full of passionate intensity.” He himself lacked political conviction, focusing his own intensity on art and family strategy rather than matters of nation or party. His rise and fall show both the terrors of revolutionary fervor, and the costs of passivity in an age where people insisted on forging their own destinies. Like the Revolution itself, it’s a very ambivalent story.

TR: I would venture to say that many Americans have never heard of John Singleton Copley. What led you to choose him as the subject for this book?

JK: If they haven’t heard of Copley, they’ve seen his work. His Paul Revere is surely the second most famous face of revolutionary America, and we see a version of it every time we hoist a bottle of Sam Adams lager. And of course, Bostonians know Copley as written into the very landscape of the city: Copley Square, the Fairmont Copley Hotel, Copley T station. But the irony is, Copley’s life doesn’t support his use in contemporary culture, which follows a kind of New England nationalism. That gap was interesting to me. Plus, the evidence is very rich: in addition to his dazzling painted work, Copley and his kin left hundreds of letters, which is true for very few artists. Those letters allowed a muddled, middling character to emerge from the swirl of events in the age of revolution. Like a Copley portrait, he’s a well mottled character. We have too few of those in the literature of revolutionary heroes and villains.

TR: In 2008, your novel Blindspot, co-written with Jill Lepore, was published. How does writing a historical novel differ from writing non-fiction? Do you think that experience influenced your writing of A Revolution in Color?

JK: Blindspot actually introduced me to Copley’s letters; Fanny Easton, the protagonist I wrote for that novel, is based in many ways on Copley. Writing a novel was a wonderful chance to think about the past in sensory and affective terms. Writing history is a more distant enterprise in many ways, but Blindspot taught me fresh ways to seek the story, and to think about reading the past forward, and from the inside out.

TR: What is your current/next project?

JK: I’m working on another biography of an artist in an age of revolution: the feminist pornographer Candida Royalle (1950-2015). It’s a departure in many ways, but has surprising continuities as well. I’m still living part-time in the eighteenth century, via a number of teaching and writing projects.